Elizabeth Harrower, The Watch Tower (1966. Text Classics 1996)

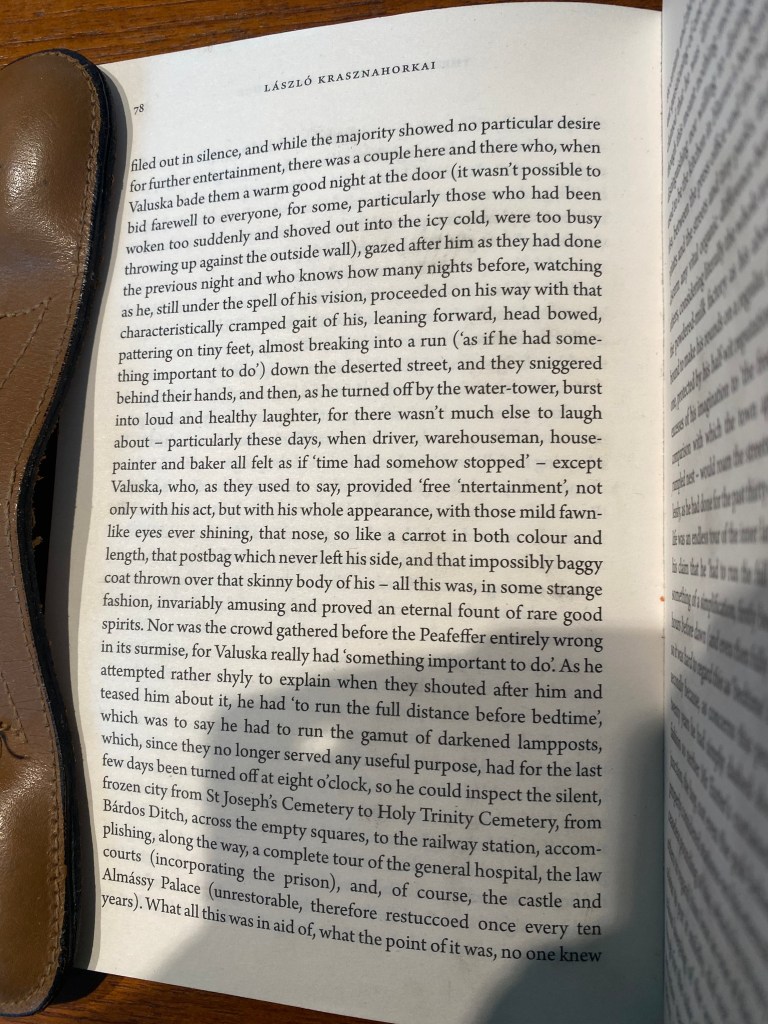

Before the meeting: I’m sticking to my resolve to write only about page 78*.

If you want a brief, thoughtful discussion of this book and its place in Elizabeth Harrower’s life work, there are plenty around. I recommend Kerryn Goldsworthy’s review, published in the Australian Book Review in 2012 (at this link). I particularly like this:

It is an accomplished and sophisticated novel of great power and intensity, but, as with most good psychological realism, the reader approaches the final pages with a sensation of exhausted, bruised relief.

It turns out that focusing on page 78 means paying attention to something I saw as of secondary interest on first reading.

This page features the book’s villain, Felix Shaw. (Sadly Elizabeth Harrower seems to have it in for Shaw men: a number of her villains have our family name.) For most of the book its main characters, Laura and Clare Vaizey, abandoned by their mother, live under Felix’s thrall, Laura as his much younger wife and Clare initially as a teenage girl in his care. There’s no romance, no love, and Felix is a misogynist in the full sense of the word – he actually hates women, and constantly torments, abuses and emotionally manipulates the two under his control.

Most of the book focuses on the sisters’ wretched servitude and isolation, but the moments when we see Felix apart from them, like this one, are interesting to revisit. Here he is giving a lift in his battered old car to a former business partner, Peter Trotter, one of a string of younger men whom Felix befriends, entering into financial dealings that invariably end up with him losing money and them leaving him in their dust as their enterprises flourish.

Felix has just explained that he is moving his office from his factory to his home. At least part of his reason, we know, is to intensify what we would now call his coercive control over his young wife. After a bit of bluster, typical rationalisation of a self-destructive action motivated by weird spite, he asks Peter Trotter’s opinion. There is a minutely observed moment of the kind Elizabeth Harrower is celebrated for.

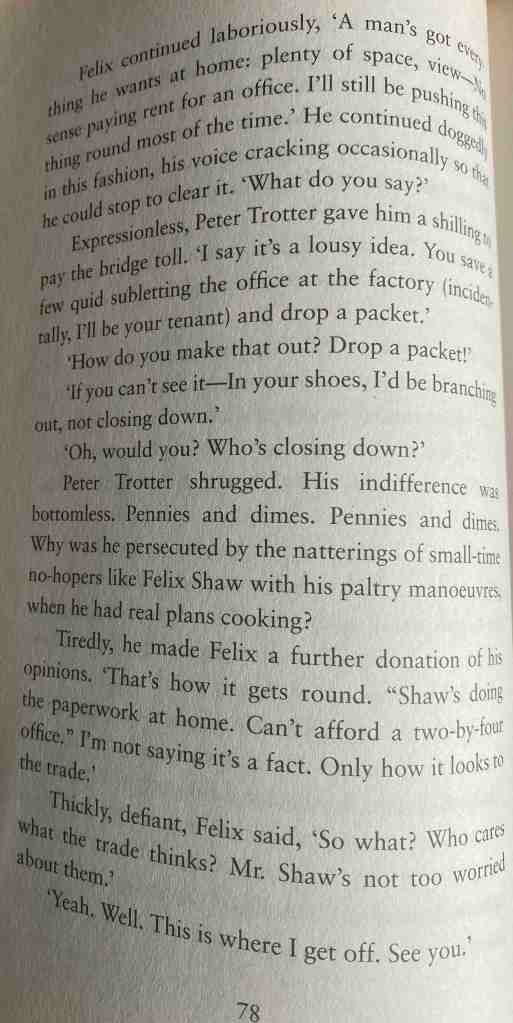

Expressionless, Peter Trotter gave him a shilling to pay the bridge toll.

‘Expressionless’ does so much work there. Even while Felix is pretending that all is well, there is this wordless abject moment when he accepts the other man’s contemptuous financial help. Then Peter offers what the reader knows is a sensible perspective, but which falls on resolutely deaf ears, while illustrating Elizabeth Harrower’s gift for vernacular dialogue:

‘I say it’s a lousy idea. You save a few quid subletting the office at the factory (incidentally, I’ll be your tenant) and drop a packet.’

‘How do you make that out? Drop a packet!’

‘If you can’t see it – In your shoes, I’d be branching out, not closing down.’

‘Oh, would you? Who’s closing down?’

Peter Trotter shrugged. His indifference was bottomless. Pennies and dimes. Pennies and dimes. Why was he persecuted by the natterings of small-time no-hopers like Felix Shaw with his paltry manoeuvres, when he had real plans cooking?

Tiredly, he made Felix a further donation of his opinions. ‘That’s how it gets round. “Shaw’s doing the paperwork at home. Can’t afford a two-by-four office.” I’m not saying it’s a fact. Only how it looks to the trade.’

Thickly, defiant, Felix said, ‘So what? Who cares what the trade thinks? Mr Shaw’s not too worried about them.’

‘Yeah. Well. This is where I get off. See you.’

And that is the end of a relationship.

This page repays a close look. Felix’s reference to himself in the third person makes me realise that Harrower’s depiction of a self-involved, wildly irrational man with bombastic self-belief and demand for absolute loyalty from those he sees as his subjects is alarmingly relevant to the mid 2020s. But it also, surprisingly to me, evokes the reader’s pity for Felix: this man we experience mainly as a controlling monster is, from another perspective, a small time no-hoper with paltry manoeuvres. This pity is dangerous: though she doesn’t use such terms, Laura, terribly abused and exploited, also sees that Felix is a small-time no-hoper, a man whose sometimes alcohol-fuelled violence is born out of deep self-hatred and lack of self-confidence, and her pity for him (she does use that word) is part of what binds her to stay with him.

None of Felix’s attempts to manipulate young men into dependency succeed because on the whole men aren’t vulnerable economically and socially the way young women are in that era. Towards the end of the book, a young male employee named Bernard collapses at work and Felix ‘kindly’ takes him into his home. At last, a vulnerable man to join his toxic household! He deploys the same emotional blackmail and bewildering switches of mood to exert control over Bernard as he has used successfully on Laura, and through Laura on Clare. There’s genuine, chilling suspense: will Bernard succumb or will he escape, taking one or both of the women with him to freedom?

Evidently publicity for the first edition used the word ‘homosexual’. I didn’t pick up any hint that Felix’s yearning for young men was knowingly sexual. But there is something forlorn in the way Felix yearns for friendship with them and in his violent rages at home when they go their indifferent way.

After the meeting: There were five of us. Three had read the whole book, one had reached the 57 percent mark on her kindle, and the fifth – who was the only one to read Joan London’s introduction to the Text Classics edition – hadn’t got that far. None of us found it a pleasant read, but the conversation was interesting.

S– saw Felix as a cipher for coercive control, and admired the way the novel was an early describer of that phenomenon, about which we know so much more now. She hadn’t read Susan Wyndham’s biography of Elizabeth Harrower, which was also prescribed reading for this meeting, and was curious to know how much the book reflected Harrower’s lived experience – it was hard to believe that she didn’t have first-hand knowledge. (A couple of us were able to satisfy her curiosity.) I would have agreed about Felix as cipher if I hadn’t lingered on page 78. I think there was more to him than that, but it’s true that the narration never takes us inside Felix’s consciousness – we see mainly the chaotic vindictiveness of his behaviour.

K– thought the book was not only painful to read but was badly written. (Gasps all round!) In her view, Elizabeth Harrower’s reputation as a great Australian novelist came mainly from her friendships with members of the Australian literary pantheon – Kylie Tennant, Judah Waten, Shirley Hazzard, Christina Stead, Patrick White. (But that’s getting ahead to the discussion of the biography.)

I talked about two moments that produced a frisson in me. The first was the chilling moment when Laura, the older sister and wife of Felix, transitions from being Clare’s ally in victimhood to being his agent in cajoling/coercing her to bend to his will. I thought this was a richly complex turn in the narrative. Others just didn’t buy it. The second was when (possible spoiler alert), starting the book’s final movement, Clare decides to give up the week escape she had been planning in order to care for the ailing Bernard. The profound ambiguity of this moment made the book come alive for me: Clare sees herself as being able for the first time to make a difference to someone else’s life, and is decides to do it with a sense of elation; but the reader sees that for years she has been coerced into putting her own needs aside to attend to Felix’s whims, and it’s simply impossible to tell whether what she sees as her new dignity isn’t a variation on the servitude she has been enduring. In my reading the remaining pages are animated by that ambiguity, and the resolution (no spoilers this time) is perfect. S– thought there was no ambiguity at all: she was just falling into the same trap with a new man.

The conversation moved on to Susan Wyndham’s Elizabeth Harrower: The Woman in the Watch Tower, about which I will blog next.

The Book Club met on the land of the Bidjigal and Gadigal clans of the Eora nation, overlooking the ocean. I wrote the blog post on Wangal and Gadigal land sheltering from unusual summer heat. I gratefully acknowledge the Elders past and present who have cared for this beautiful country for millennia, and welcome any First Nations readers of this blog.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.