Chris Mansell, Foxline (Flying Island 2021)

Chris Mansell is an Australian poet with an impressive list of books and awards to her name. She has also played a significant role in fostering and publishing other poets. Here’s a link to her website. Foxline is part of Flying Island’s Pocket Poets Series, small enough to fit into a shirt pocket, but offering a substantial reading experience.

The book’s last page has a note describing its genesis:

I came across a fenceline of foxes scalped and strung by their hind legs on the boundary fence of a farm. There were about two hundred dead and even dead they were beautiful. … I imagined the farmer, perhaps less articulate than the fox. I imagined him walking the paddocks in stolid opposition to the creatures that were taking his sheep.

It is real and it is also traditional. It is in his blood as it is in the blood of the fox to hunt and feed their young.

Each of the book’s 30 poems is spoken by the farmer or a fox. In most of the fox poems the speaker is a female fox; occasionally we hear from a young male, and even once or twice a flying fox. Both Fox and Man (they are capitalised in the marginal notes) are interested in more than each other, but mainly the poems deal with their relationship: their antagonism, their attempts to understand each other, and their recognition of what they have in common. They even manage to learn from each other.

In one poem (‘Dark Solo’) a young male fox becomes the fox in Ted Hughes’s poem ‘The Thought-Fox’. But the literary work I was most strongly reminded of is Roald Dahl’s The Marvellous Mister Fox. In some ways Mansell’s book could be read as an adult response to Dahl’s. Here there is no easy resolution to the conflict between Man and Fox and, contrary to what you might expect from Mansell’s account of the book’s origins, both characters elicit our sympathy.

Before I talk about page 77*, I want to name my favourite stanza in the book. It’s the beginning of ‘Surprise’, one of the Man’s poems, and is a haiku-like stanza (or more accurately senryu-like, as haiku aren’t supposed to mention people):

we are always surprised

here every winter

we are amazed it's cold

The poem goes on to arrive, elegantly, at how we are ‘astounded / by death especially’. I love the way the poem makes poetry from an often-heard New-South-Wales joke, then takes it somewhere unexpected but completely right.

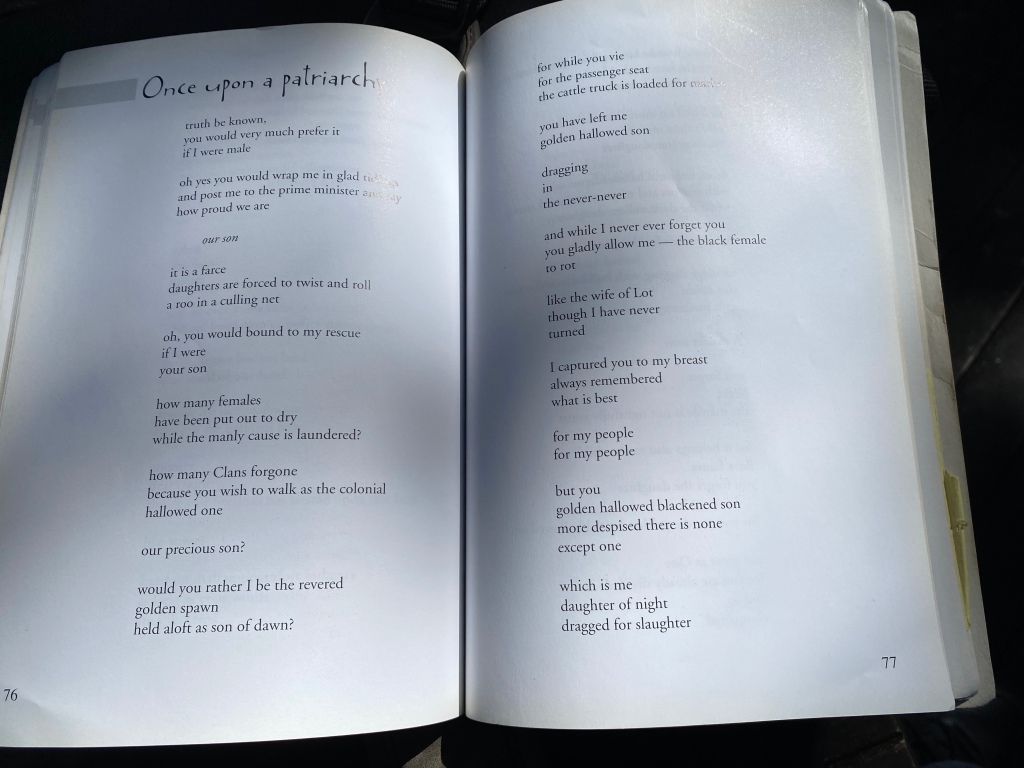

Page 77 is the beginning of the poem, ‘He relates their conversation’.

HE RELATES THEIR CONVERSATION

Like every poem in the book, this one has a note in the margin telling us who is speaking and offering a brief summary, the way some 18th century novels do, as if acknowledging that the semi-articulate protagonists don’t always make themselves clear:

The Man recounts the Fox's wisdom

The italics on this page signify that though the Man is speaking, he is relating the Fox’s words. The Fox’s ‘wisdom’ is paradoxical:

fox says sometimes of our friendship

I think it is failure that keeps

us together

In what way are they together? And whose failure does she mean? An obvious meaning is that ‘together’ really means ‘both alive in the same locality’, and the failure is that of the Man – he has failed in his quest to kill the fox. But the word ‘friendship’ in the first line suggests that something else is going on. Its cryptic possibilities provide the impetus to read on.

that I should fail in certain ways

be unkept and poor to be less

approved of in the field

Before she gets to ‘friendship’, the Fox expands on what she means by ‘failure’. She is the one who must fail. To understand ‘in certain ways’ we don’t need to think beyond the Fox’s activity as sheep-killer. If she succeeds in killing or even damaging the Man’s livestock that’s the end of any fellow-feeling. ‘Unkept’ is an example of the way the Fox’s language is interestingly off-kilter throughout the book. It’s not quite ‘unkempt’ though it possibly includes that. It suggests the opposite of ‘well-kept’ as in well-fed. The fox needs to be bad at her job – ‘less / approved of’ in the field’ by other foxes, perhaps.

you have the rifle your freedoms and fiefdoms are what you choose_ your limits and your boundaries are bought owned certified and succinct

(The double space in the third line here acts as a break in the meaning – a full stop.) But yes, the Man must also fail in his quest to eliminate the fox. He has the means, but he can choose to act freely or according to an imposed order. ‘Freedoms and fiefdoms’ is a wonderfully evocative phrase: is this farmer a free operative or is he pretty much a serf in the current economic order? It’s his choice. the limits and boundaries are those of the farm, but they are also limitations and constrictions on himself that he has bought into.

I wear the orange and you the black

On first reading, I had no idea what this meant. Now that I’ve pondered the previous lines, its meaning leaps out at me. The Fox is making an analogy to sporting teams – Australian cricketers wear the baggy greens, Indians the bleed blues. The Fox and the Man belong on different teams.

I won’t go on in detail about the remaining page and a bit. In short, the man now speaks in his own voice, expressing a wish to become the Fox, and they recognise the similarity between the rifle and the fox’s ‘whitesharp teeth’. According to an explanatory side note:

They know

they have a

tense

commonality

‘Tense commonality’ is an excellent human-prose translation of the Fox’s term ‘friendship’.

* My blogging practice is to focus arbitrarily on the page of a book that coincides with my age. This page often reveals interesting things about the book as a whole.