Sunday was another beautiful late autumn day in Sydney, and another day of challenge and delight at the Sydney Writers’ Festival. Evidently one of our ideologically driven weeklies ran a piece online saying the Festival was extremely ‘woke’, which is apparently a bad thing. I don’t know about woke but, as someone who nods off whenever I’m in a dark room, I was kept awake almost without fail. (The one fail was inevitable, in the after-lunch slot when I would have slept through an announcement that I’d been granted the gifts of immortality and eternal youth.)

10.30: Land of Plenty

This panel addressed environmental issues about Australia from a range of perspectives. Philip Clark of ABC Radio’s Nightlife did a beautiful job as moderator, giving each of the panellists in turn a prompt or two to talk about their work, and managing some elegant segues. The panellists did their bit to make it all cohere by referring to one another’s work. (How much better these panels work when the panellists have read one another’s work!)

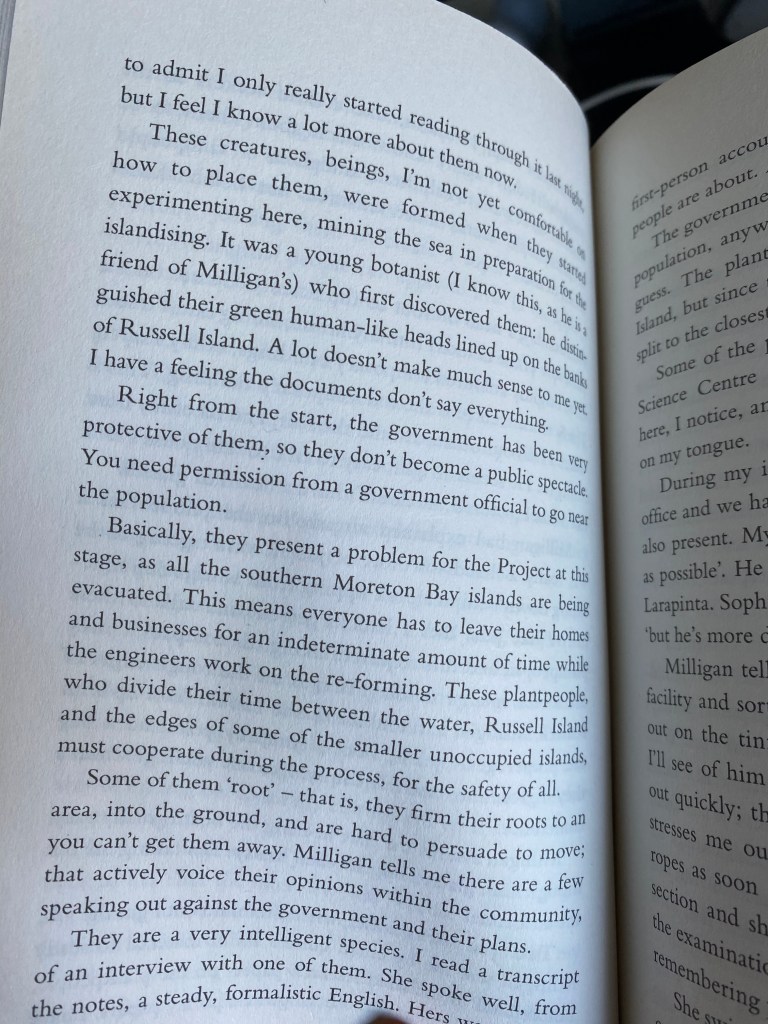

Rebecca Giggs, whose Fathoms sounds like a fascinating book about whales, said that whales are a Trojan horse for a conversation about other animals’ relationships to humans. She described a moment when she was close enough to a whale that she could see its eye focusing on her – and only to learn a little later that whales are extremely short-sighted and there as no way that that whale could have actually seen her. What is actually there isn’t what we want to think is there,

Bruce Pascoe, author of Dark Emu and co-author of Loving Country (about which more later) spoke about the difference between Indigenous and Western capitalist ways of relating to the land. Echoing Rebecca Giggs’s story of the whale’s eye, he said, ‘We look at animals and want to be friends with them, but as soon as a capitalist wants to be your friend …’ He begged us to take seriously the possibility of a reciprocal relationship with animals. Something terrible happened to humans, he said, when the combination of Christianity and capitalism happened. I think he has a book coming on the subject.

Victor Steffensen is a Tagalaka man from far north Queensland, author of Fire Country. Someone from my family had the privilege of doing some video work with Victor some years ago, and his stories from that time have given me a deep respect for Victor and his work in ‘using traditional knowledge for environmental wellbeing’, as the Festival site puts it. In this panel, he took off from Bruce Pascoe’s call for reciprocity with other animals, and spoke of relating to fire as a friend and not as something to fear. It’s about reading country, listening to landscape. His project of recording traditional knowledge that is in danger of being lost is not to archive it but to get it back into people, ‘to young fellas and then to the broader community’.

Richard Beasley, senior counsel assisting for the Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission and author of Dead in the Water about that catastrophe, said that the situation in the Murray-darling Basin had got so bad that ‘even John Howard’ did something about it. Howard’s legislation included clauses to the effect that whatever was done needed to be science-based. But then the lobbyists went to town, and in response to their pressure, politicians insisted that reports from the CSIRO were altered to suit the big capitalists’ agenda. His lawyerly rage was palpable.

There was a good question (a rarity at this Festival), about grounds for hope:

- Rebecca Giggs: Thee’s hope. But you don’t get to be hopeful until you make yourself useful in some way – whatever your situation and abilities allow.

- Bruce Pascoe: I have to think we can do it differently. We have to give our grandchildren a chance, not treat them with contempt. We need love of country, not nationalism.

- Victor Steffensen: Language is important. [Sadly what I wrote from the rest of what he said was illegible. I think it was an elegant version of ‘Action is also important.’]

- Richard Beasley: I’m a lawyer. I don’t know how to challenge any of this by law.

12 o’clock: Sarah Dingle & Kaya Wilson

We hadn’t booked this session in advance, but faced with a gap of a couple of hours, we spent one of our Covid Discover vouchers to buy rush tickets. Kaya Wilson, whose book As Beautiful As Any Other has the subtitle A memoir of my body, is a tsunami scientist and a trans man. Sarah Dingle, author of Brave New Humans: The Dirty Reality of Donor Conception is a donor-conceived person. Their conversation was aided and abetted by Maeve Marsden, host of Queerstories who was also donor conceived, though not anonymously through the fertility industry as Sarah was.

Sarah’s revelations about the fertility industry were nothing short of shocking. Not only is it monumentally unregulated, but records that might have allowed people to know what had happened to a particular donor’s sperm, even anonymously, have at least sometimes been deliberately destroyed. Couples using donated sperm have been systematically encouraged to lie to their children about their origins, leaving them unaware of any genetic predispositions to disease, let alone possible incest.

What Kaya told us about the systemic treatment of trans people was just as shocking. He said that he tended to keep his scientific life and his trans life separate. ‘In some ways they hate each other.’ But he has a chapter in his book that tries to reconcile them. The scientific literature, like legislation about, for instance, changing one’s ‘sex marker’ on a birth certificate, is shot through with assumptions that bear not relation to the reality of trans experience.

Both people spoke of the joy of finding themselves to be members of communities they weren’t aware of when young. When asked what they read for relief, both named writers I’ve loved: Sarah chose Terry Pratchett; Kaya chose Ocean Vuong, On Earth We Are Briefly Gorgeous.

2.30: Bruce Pascoe & Vicky Shukuroglou

Loving Country: A Guide to Sacred Australia was an initiative of Hardie Grant Publishers, who approached Bruce Pascoe suggesting a follow-up to Marcia Langton’s guide to Indigenous Australia, Welcome to Country. Pascoe joined forces with Vicky Shukuroglou, a non-Indigenous woman born in Cyprus, who took the photographs and also contributed to the writing. The Festival website says that the book ‘offers a new way to explore and fall in love with Australia by seeing it through an Indigenous lens’. Daniel Browning, host of ABC Radio National’s Awaye, chaired this conversation.

Again, we were called on to love this country. The thing I loved about the session was the way the two authors could disagree. Bruce Pascoe, speaking of the horrendous bushfires last year, said that the disrespect for Country shown by authorities afterwards was in some ways worse than the fires themselves. We meekly accept the terrible destruction of heritage in the Juukan Gorge. We have to rebel as a people, he said, meaning all of us, not just First Nations people. Vicky Shukuroglou argued against the idea of rebellion, and spoke of the importance of conversations and of love: ‘If we’re going to talk about marginalisation, we first need to look at our humanity.’ From where I was sitting it didn’t look as if the two things were incompatible, but I was struck by the way as a non-Indigenous woman she was secure enough in their friendship and working partnership to challenge an Indigenous man. I would have liked to know more about what she had done to achieve that confidence.

The book, Pascoe said, is about how to restrain human go and let Country have a voice, He got Vicky to tell a story about a sick echidna that, without her realising it, had come to know and trust her, as a result – she thinks – of her being still around it over time.

We don’t need a black armband.

We just need to know the facts.

This is the country that invented society, bread and the Richmond Football Club.

4.30 pm The Unacknowledged Legislators

This was a great way to end my festival. (The Emerging Artist’s festival ended with the previous session: she thinks poetry and she don’t like each other.) Seven poets read to us, hosted elegantly by ‘writer, poet, essayist and proud descendant of the Yorta Yorta’, Declan Fry. Here they are, in order of appearance.

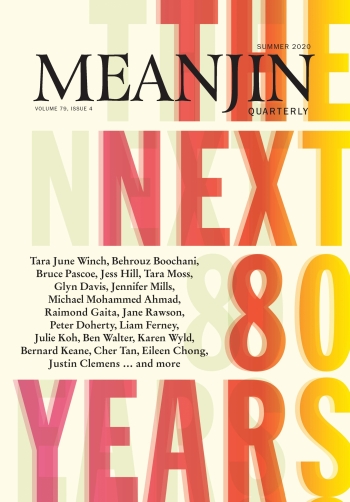

Eileen Chong, whose poetry my regular readers will know I adore. She read five poems from A Thousand Crimson Blooms, which I’ll be blogging about soon. I was glad to hear her read the three part poem, ‘The Hymen Diaries’ after I had spent some time with it and checked out the artworks it refers to.

Maxine Beneba Clarke, poet laureate of the Saturday Paper, read three poems. I won’t report what they were because i wasn’t sure I heard their names correctly. One of them began, ‘When I say I don’t want to become my mother,’ and went on brilliantly to challenge the internalised sexism of that sentiment.

Ellen van Neerven read three poems from Throat (my blog post here), including ‘Treaty of shared power’ and ‘Such a sad sight’. The first-named is a play on the relationship between the writer of a poem and its reader that worked beautifully in this context.

Erik Jensen, reading to an audience for the first time, read six short poems from his first book of poetry, I said the sea was folded, a book that, he told us, is about falling in love and learning to be in love. He then read a poem by Kate Jennings, who has just died (this was how I heard the news) – and wept as he read it. He wasn’t teh only one to shed a tear.

Felicity Plunkett followed that hard act, reading four short poems from her 2020 collection, A Kinder Sea. The first, ‘Trash Vortex’, whose name tells you a lot, may be the kind of poem that Evelyn Araluen had in mind when she said artists have a responsibility to address the world’s urgent issues.

Omar Sakr read three poems, ‘Birthday’, Self-portrait as poetry defending itself’ and ‘Every Day’. This is the first time I’ve heard or read any of his poetry. I hope it won’ be the last.

Alison Whittaker, Gomeroi woman and a crowd favourite, read a piece that depended on knowledge of and (I think) contempt for ASMR, not that there’s anything wrong with such poems. She reminded us of the tragic reality of Black Deaths in custody and read a poem consisting of anodyne found phrases from court proceedings.

And my 2021 Sydney Writers’ Festival was over. There were at least four moments when someone on stage paid tribute to a parent in the audience or, in one case, on stage with them (I’d left my run too late to see Norman and Jonathan Swan, and I probably missed other trans-generational moments). I didn’t see any of the international guests who attended on screen. It was a thrill to hear such a diversity of First Nations voices. I came home with a swag of books and a list for borrowing from the library. Hats off to Michael Williams and his team for making this happen in the flesh, and making sense of the slogan Within Reach: a living demonstration that the famous cultural cringe, while it may not be dead, has not much reason to live.