Michelle Johnston, The Revisionists (Fourth Estate 2025)

Before the meeting: Michelle Johnston’s day job is in emergency medicine. According to a 2023 interview on ABC Perth, she had written a draft of this novel when she decided that she had to go to Dagestan, a small republic in south of Russia where most of the novel’s action takes place, because ‘if you’re going to write somebody else’s story, you’ve got to respect it by going there and trying to understand it from the ground level up’. It was risky – DFAT advised against going and the Smart Traveller website warned of possible terrorist attacks – but she went out of dedication to the integrity of her writing, and in fact ‘had the most beautiful trip’.

The novel’s main character, Christine Campbell, doesn’t have such a beautiful trip, though the book captures the physical beauty of the place and the wonderful hospitality of its people. Christine is a journalist. Disenchanted with what Western Australia has to offer including an implausible level of sexism in Perth’s newsroom, she decides to travel to Dagestan to join Frankie, her best friend from schooldays who is a doctor working in a clinic in a tiny village there. Christine is there to help – she organises supplies and teaches first aid to local women – but she harbours an ambition to publish a groundbreaking piece of journalism about the possible outbreak of war.

It’s an odd set-up. We know from the beginning that Christine’s ambitions outstrip her abilities, and that her journalistic ethics are shaky. She intuits that the women of the village know that war is coming, but she can’t get them to say it outright. In fact everyone knows there’s a serious risk of war. It’s 1999: the war in neighbouring Chechnya ended in 1996, armed Islamist groups are forming everywhere, Russia is determined to fight them off, and the place, as Christine keeps saying, is a ‘tinderbox’. But she’s determined to write a feminist-leaning piece in which she gives voice to the women of the village saying what she just knows they would say if only they would say it. Her article will be titled ‘The Cassandras of the Caucasus’, because she believes the classical allusion will lend it class. (And the samples we see of her over-egged writing are consonant with that kind of thinking.) Frankie hints that she might expose the women to the danger of reprisals. She meets a famous journalist who gives her some Journalism 101 advice that seems to be news to her: if you’re out to get information from people, tell them up front that you’re a journalist.

The book opens in Manhattan 25 years later, in 2023, with Christine watching a TV documentary about herself and the one article that made her famous. A little later, Frankie turns up at her door, and challenges her about the untruths she told in the documentary and in the famous article. As the book proceeds, alternating between the two time periods, we learn the full story of how the article came to be written, and the fate of the Dagestan village. Revelation follows revelation. Christine’s ethics are a lot worse than shaky.

The book tackles important subjects: journalist ethics, the nature of memory, the role of ‘helpful’ but insensitive Westerners, the question of who owns a story. There’s a strong sense of place, not only in the austere beauty of Dagestan, but also in London where Christine and her friends have a brief respite, and Manhattan where she spends more than two decades in guilt, luxury and inertia.There’s a tumultuous affair with a man that we know is up to something, and a painfully real portrait of an unhappy marriage

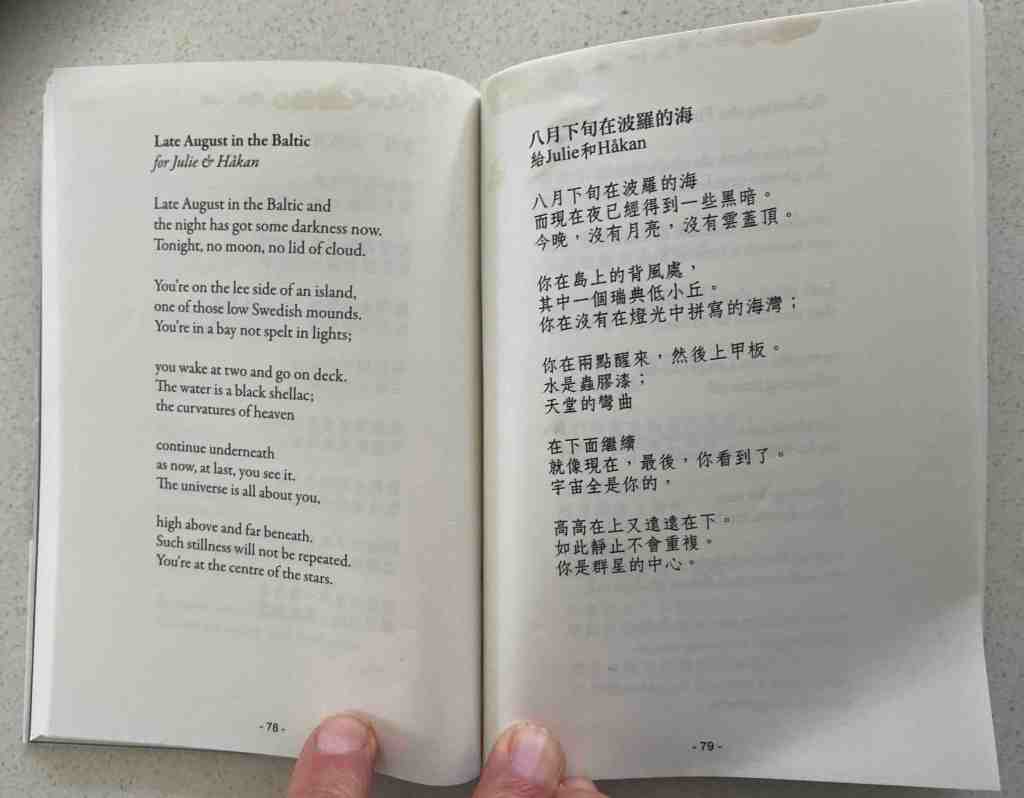

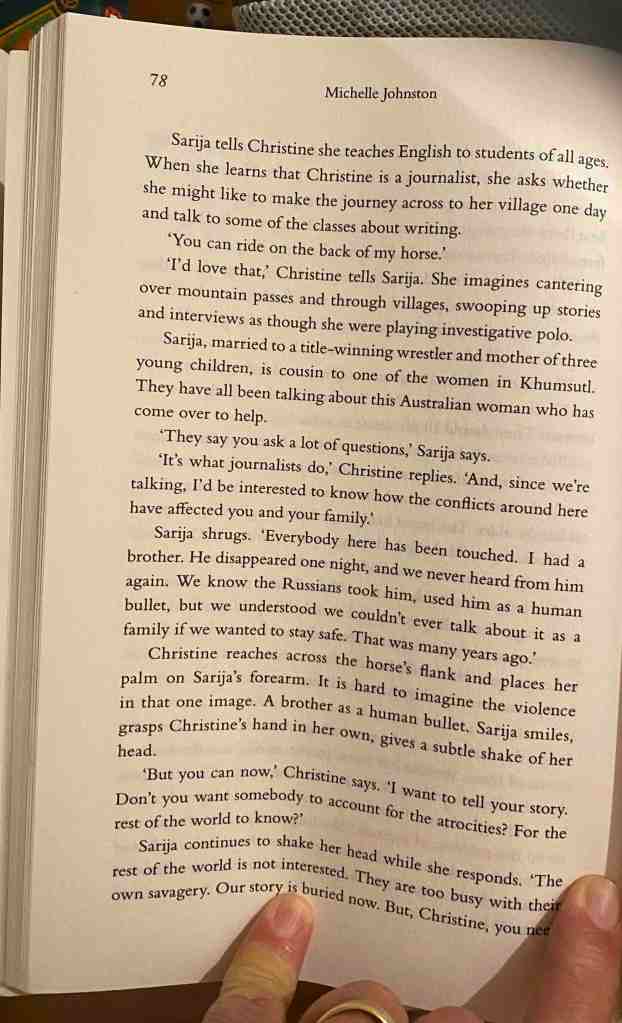

On the strength of all that, you’d think I would have been engrossed. But I struggled with it, and it’s not easy to say why. It turns out that a close-ish look at page 78* suggests a possible reason.

Sarija is a teacher of English from a nearby village who has attended Christine’s first-aid classes, and even acted as her assistant. Here, the two women are chatting, leaning against the dusty haunches of Sarija’s horse. Sarija suggests that Christine might visit her village to talk to her students about writing:

‘You can ride on the back of my horse.’

‘I’d love that,’ Christine tells Sarija. She imagines cantering over mountain passes and through villages, swooping up stories and interviews as though she were playing investigative polo.

This is an example of many similar moments. I would have said it hits a false note: why would Christine, formerly Crystal from the WA wheat belt, think of polo? Surely the forced simile is an awkward writerly intrusion? On rereading, I see it differently. What’s happening is that the narrative voice, while technically telling the story from Christine’s point of view, looking over her shoulder as it were, actually undermines her, mocks her as callow, exploitative, self-serving, in effect accusing Christine of thinking of her journalistic quest as a jolly sporting venture.

There are more examples even in this one page of dialogue.

‘They say you ask a lot of questions,’ Sarija says.

‘It’s what journalists do,’ Christine replies. ‘And, since we’re talking, I’d be interested to know how the conflicts around here have affected you and your family.’

This is a woman who has been uncomplainingly lugging boxes around the clinic, winning the trust of the local women as she teaches them first aid. As soon as she thinks of herself as a journalist she becomes patronising (‘It’s what journalists do’) and would-be exploitative (‘Since we’re talking…’).

Sarija opens up to her anyway. Again, Christine makes a small gesture of sympathy, but her mind goes to the juicy turn of phrase:

It is hard to imagine the violence in that one image. A brother as a human bullet.

‘I want to tell your story. Don’t you want somebody to account for the atrocities? For the rest of the world to know?’

Sarija continues to shake her head while she responds. ‘The rest of the world is not interested. They are too busy with their own savagery. Our story is buried now. But, Christine, you need to know this: you don’t find answers here by asking questions.’ She pauses. ‘You find the answers by being quiet.’

To which this reader, led by the narrative voice, wants to shout, ‘Yair, Christine. Be quiet.’

Later, when Christine is frustrated at the lack of usable quotes from the women, she thinks back to this conversation and sees Sarija as her likeliest source of good copy. There may be some truth to this portrait of journalism in the field, but when she’s being a journalist Christine is almost completely unlikeable. Later, when she manages an interview with a self-styled warlord, she castigates herself for doing something terrible with what she has been told. The narrative voice holds back from condemning her, so even when she’s hard on herself, she is seen to be missing the point. She does commit one major journalistic sin, and in that case goes from self-deception about the gravity of her offence to wallowing in shame and remorse.

Though Christine goes on to make amends in some respects, I get the impression that Michelle Johnston doesn’t like her main character – and that makes a book hard to read.

Other people like this book a lot more than I do. Lisa Hill’s review is definitely worth reading.

Just before the meeting: We read two books at each meeting of the Book Club. The Revisionists was paired with Susan Choi’s Flashlight, and the comparison wasn’t kind to The Revisionists. For just one thing, both books deal with terrible historical events. In her acknowledgements, Susan Choi lists fifteen books of fiction and non-fiction about her subject so the reader can check how closely her fiction sticks to known facts. Michelle Johnston tells us nothing about her sources. This might not have mattered, but when there is an unreliable central character, it would be good to know if two atrocities in particular were invented for the horror of it or were documented events.

After the meeting: We were pretty unanimous in not caring for this book. Not everyone agreed that the author didn’t like her central character – what I saw as criticism of her as callow and exploitative, others saw as ironic highlighting of her naivety. But none of us much liked her anyway. One person went so far as to say the book shouldn’t have been published. Someone who has visited New York City quite a lot was exasperated that when Christine decides to sell a Rothko that has come into her possession, she takes it to a local gallery. ‘I’m sorry,’ she said, ‘if you have a Rothko to sell you go uptown to Christie’s or Sotheby’s.’ Rookie error, I guess.

We pondered the meaning of the book’s title. Perhaps it refers to the way Christine altered some key facts in her famous article. Perhaps it highlights an otherwise inconsequential moment in the last pages when Frankie and Christine realise they have completely different memories of how Christine came to be in Dagestan. We also pondered the meaning of the cover image: two women in profile, both with the abstracted air of models. None of us could see how it related to the actual novel.

On the other hand we had culturally eclectic creations from Tokyo Lamington for dessert, and Flashlight (blog post to come) is an excellent book that provoked interesting conversation.

The group met on the land of Gadigal and Wangal of the Eora Nation, where I have also written this blog post. The days are getting longer, and warmer, and I’ve been encountering a beautiful, satiny crow near my home. I acknowledge Elders past and present, and welcome any First Nations readers.

* My blogging practice is to focus on the page that coincides with my age, currently 78.